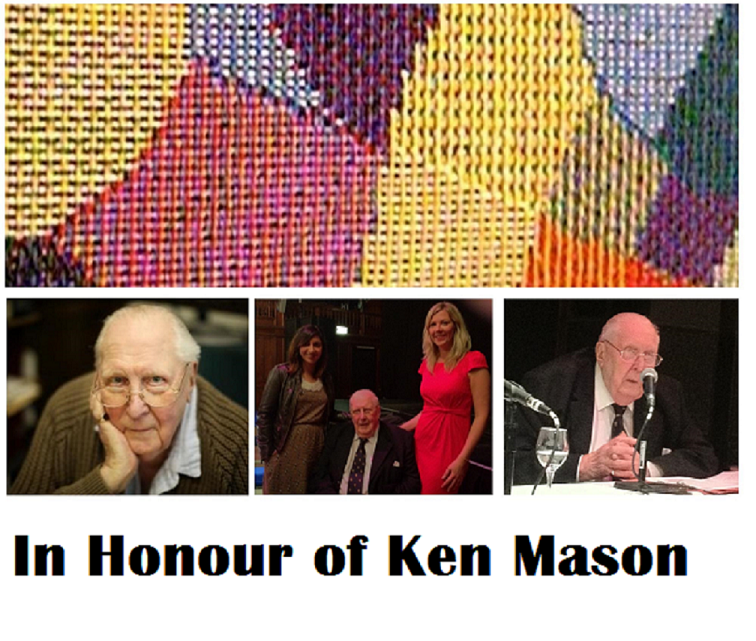

On these pages we honour the intellectual contributions of our esteemed colleague and dear friend, Ken Mason, in the broad field of medical jurisprudence. We invite short academic posts up to 1,000 words that are inspired by Ken Mason’s writing in the field. Anyone who knew Ken or has been influenced by his work is welcome to submit a proposal to Graeme.Laurie@ed.ac.uk.

Ken Mason was an Honorary Fellow in the School of Law at the University of Edinburgh for 32 years, from 1985 until his death on 26 January 2017. Even before joining the School of Law officially, Ken was publishing significant contributions in medical law and ethics during his time as Regius Professor of Forensic Medicine, also in Edinburgh, from 1973-1985. During that early period he established honours and masters courses in medical jurisprudence with his colleague Alexander (Sandy) McCall Smith, and this work formed the basis of their textbook, Law and Medical Ethics, that was first published in 1983. It was the first such textbook of its kind in the United Kingdom and helped to establish Ken Mason has an unassailable founding father of the discipline in the UK. The book has been used by multiple generations of undergraduate and postgraduate students since its first appearance, and many of Ken’s former students offer contributions on these pages that speak of the ways in which Ken and his intellectual ideas have inspired them.

Ken Mason was a prodigious scholar. He was fascinated by all aspects of medical law and ethics, which in Edinburgh we call Medical Jurisprudence. This both reflects the historical links between medicine and law that have existed in our institution since the 18th century, and also captures the idea that our field transcends disciplines and requires input across different specialities to make genuinely influential contributions. While Ken’s command of the law was often superior to that of many of his legal colleagues, his interests were particularly engaged by reproduction & the law, as well as by end-of-life issues. True to form, however, Ken was always open to changing his mind. It was not unusual from one academic year to the next for colleagues to be wrong-footed by a 180-degree volte face by Mason on any given topic! On more than one occasion, he declared himself a feminist - as much to his own surprise as to anyone else’s.

Still, Ken often professed to having a ‘bee in his bonnet’ about stubborn issues and questions in medical jurisprudence. In particular, we recall the following:

- he strongly supported the view that a mature minor should not be allowed to refuse treatment, even is she has capacity to consent (Gillick)

- he took issue that that law affords the fetus ‘no rights’;

- he was vexed by the ‘individualistic’ turn in medical law, and was drawn to notions such as relational autonomy;

- he often called himself a communitarian, and he was intrigued by areas of law and ethics that reflected this idea;

- he was engaged by assisted dying legislation, especially on what would count as adequate safeguards and whether medical practitioners should be involved;

- he insisted that death was a process, and not a moment, and he was frustrated by law’s failure to reflect this: this has implications for his view on transplantation;

- he vehemently disagreed with the rule that you cannot recover for the birth of a healthy child even when there is negligence;

- he would have been fascinated by the current revisitation of the 14-day rule in embryo preservation and use.

You will find contributions here that reflect these and many other of Ken Mason’s ideas. As stated above, we welcome contributions from anyone who knew him or his work. As a reminder, here are some links to Ken’s contributions to medical jurisprudence over the years as well as to other examples of the work of people who have honoured him:

-Ken Mason's publication list on Edinburgh Research Explorer

-Ken Mason’s monograph, The Troubled Pregnancy (CUP, 2007)

-Ken Mason’s festschrift, First Do No Harm (SAM McLean (ed), Ashgate, 2006)

We will continue to populate this site with contributions as and when the come in. We will alert audiences via the Mason Institute and its Twitter account @masoninstitute.

If you would like to contribute, please contact Graeme.Laurie@ed.ac.uk

If you would like to become a member of the Mason Institute, please contact Annie.McGeechan@ed.ac.uk

If you would like to leave a message of condolence, please visit the official site here: www.inmemoryofkenmason.law.ed.ac.uk

Please scroll down this page to read our latest blog posts.

Tuesday 14 March 2017

Continuing the Intellectual Legacy of JK Mason: From Autonomy to Vulnerability and Beyond

Reflections on a motley coat

I still remember very clearly the first time that I met Ken. It was

the introductory seminar of my LLM module in Medical Jurisprudence.

Whilst having such a wide array of fascinating topics to discuss each

week already felt like a treat, the real show-stopper for my fellow

classmates and I was having an 89 year old Professor teach us. And not

just any 89 year old Professor, but THE Ken Mason, ‘Ken the legend’ as

he soon came to be known amongst us. I so looked forward to Wednesday

morning seminars, to hearing what Ken had to say about all of the

challenging topics that we covered (particularly on reproduction and

assisted dying), to watching him debate with his colleagues (sometimes

with a mischievous argumentative glint in his eye), to chatting with him

over the coffee break, to which he insisted bringing for the class a

variety of chocolate biscuits, tea and coffee and his beloved kettle,

still going strong since the 1970s we guessed.

I still remember very clearly the first time that I met Ken. It was

the introductory seminar of my LLM module in Medical Jurisprudence.

Whilst having such a wide array of fascinating topics to discuss each

week already felt like a treat, the real show-stopper for my fellow

classmates and I was having an 89 year old Professor teach us. And not

just any 89 year old Professor, but THE Ken Mason, ‘Ken the legend’ as

he soon came to be known amongst us. I so looked forward to Wednesday

morning seminars, to hearing what Ken had to say about all of the

challenging topics that we covered (particularly on reproduction and

assisted dying), to watching him debate with his colleagues (sometimes

with a mischievous argumentative glint in his eye), to chatting with him

over the coffee break, to which he insisted bringing for the class a

variety of chocolate biscuits, tea and coffee and his beloved kettle,

still going strong since the 1970s we guessed. A few years on, we set up the Mason Institute in Ken’s honour. We named the Mason Institute blog ‘the Motley Coat’ after Ken’s inaugural lecture entitled ‘Ambitions for a Motely Coat’. I am sitting with a copy of the transcript of that lecture, delivered on 28th February 1974, open beside me as I write. Ken borrowed the title, taken from Shakespeare’s As You Like It, in which he starred as Jacques in a school production many years earlier. Ken reminded those attending his lecture that in the play, Jacques met a jester who impressed him, upon returning to his friends, Jacques proclaimed:

‘and in his brain,

which is as dry as the remainder biscuit after a voyage,

he has strange places crammed with observation,

the which he vents in mangled form

‘Oh!’, said Jacques, ‘oh! That I were a fool; I am ambitious for a motley coat.’

Ken concluded his lecture with the following words:

‘I have tried to show you some ways in which I would hope to justify my appointment by transforming the rather monochrome, unvarying cloth of traditional forensic medicine into what I believe to be a fresh, multicoloured and multi-directional motely coat of community service, resting on a broad base of service to the community in general and the police in particular, fed intellectually by contact with the students of many disciplines and extending arms which genuinely welcome and are anxious to provide a full service of co-operation’.

Given the numerous and vast contributions which Ken made throughout his academic career, it is safe to say that he was certainly successful in his endeavour of transforming forensic medicine into a fresh, multicoloured and multidirectional coat.

Ken was also very much successful in extending his arms out to students and colleagues alike. He was particularly generous with his students, whom he inspired, adored and indulged with endless patience and enthusiasm. I’d often leave his office with another book which he thought I might find interesting, or a new angle to explore in my work, and always with the feeling that my own thoughts and perspectives mattered too. He was constantly encouraging and very much open to genuine debate. He taught me that even after 97 years, it is perfectly acceptable to say ‘I don’t actually know the answer to that’ or ‘perhaps I have changed my mind’, and the importance of listening to others, always with respect.

I remember the first time that I visited Ken in his office, no longer as a student but as a colleague, the year following completion of my LLM. I knocked on his office door one lunchtime, and was greeted by Ken, sitting in his chair, with the cricket blaring on the radio in the background. He was

nibbling away at some of his favourite Jamaican ginger cake. Every so often he would like to have a little rant (ranging from deeply philosophical musings, right up to trivialities on the diminishing quality of Jamaican ginger cake). Often such rants were premised with ‘the only bee in my bonnet is...’.

It transpired that Ken had quite a few bees in his bonnet, all of which were a delight to hear about. His reflections and observations were so insightful and more often than not, injected with a good dose of Ken’s signature humour. Alongside his ability to laugh and to make others laugh, in all of our conversations, no matter what the topic, no matter how Ken was feeling, he approached his colleagues and students with openness, humility and kindness. What also struck me about these rants was that Ken would often end them with a question, he honestly wanted to know what others thought, he was just as interested in listening to and learning from others as he was in sharing his own opinions.

I was always so impressed with Ken’s eagerness and tireless efforts to keep abreast of the latest developments in medical jurisprudence, particularly when office visits turned into home visits. He was keen to discuss the latest case law or journal articles over a few glasses of Bombay Sapphire (indeed that’s when the discussions became even more interesting!)

Ken had so many bees in his bonnet because he genuinely cared, he genuinely wanted to make an impact, to continue in his service to the community. This was evidenced after his ‘official’ retirement, which really only meant that he ceased teaching and continued to write from home. Ken never ceased in transforming the motley coat. I look forward to working with colleagues within and beyond the Mason Institute, in continuing Ken’s legacy, inspired by his dedication to transformation, multidisciplinarity, dialogue, engagement with students, open arms and community service. Now what bee is in your bonnet?....